Learn more about this series.

INSTAGRAM

(A cautionary tale)

(A cautionary tale)

|

Abby Kirsch, GRHS Class of 2020, is an Information Design and Corporate Communications major at Bentley University. Avid Croc enthusiast, Red Bull lover and Squishmallow plush toy collector, Abby is among the first generation to grow up in the age of social media.

|

|

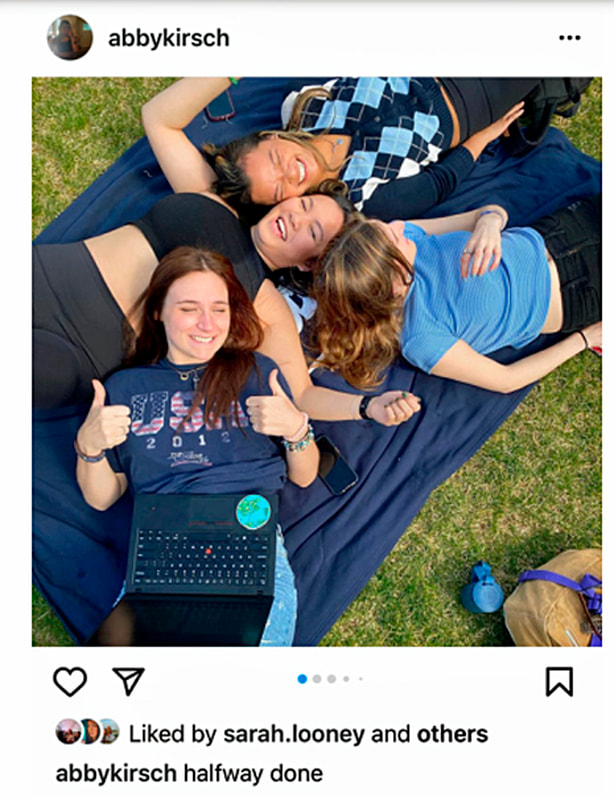

At age 11, I was allowed to create an Instagram account on my iPod Touch. The account was a fun, safe place where I could share my fifth-grade life with my friends and also see, through their posts, their lives unfolding. This seemed like a huge win.

I wanted an account the way children want a new toy, pet, or the latest iPhone. All it took for my mom to cave was some endless nagging on my part and a few restrictions: that my account was private, I didn't use my full name, and that she could monitor my followers. I gladly obliged; this was a small price to pay for me to enjoy this fun, new form of interaction. By 8th grade, fake Instagram accounts (“finstas'') with clever and ironic usernames quickly became the go-to source for gossip at GR Middle School. Original Instagram accounts were for showing the best of your life. Finsta accounts were for sharing with one’s closest friends, taking on the role of a diary. Even before social media, kids kept their diaries hidden, especially from parents. Now they did the same with their finstas, allowing us to post the most unfiltered parts of our lives and thoughts with no parental monitoring and no repercussions. My friends and I became too comfortable with sharing absolutely everything about our middle school lives and talking negatively about our peers, turning these finstas into accounts of exclusion. Posts spread like wildfire among us – young girls who were the first generation to grow up in the age of social media – and just like a wildfire, caused great damage.

One day, while mindlessly scrolling through my Instagram feed and doing my Social Studies homework, I refreshed my page to see newly posted pictures of my “friends” laughing, bonding and having a great time hanging out – without me. My skin started heating up, my eyes were watery, and my hands and legs were trembling. Sitting at home, alone and uninvited, brought on one of my first anxiety attacks. I couldn’t process how I was feeling. I felt burned, that’s all I knew. Why did they not want me there? Unintentionally burning myself deeper. The scar left by that burn read, “Lonely.”

I just wanted to crawl into a ball and never face the outside world ever again. Did I even know who my true friends were? Would I ever find my people? FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) became – thanks to Instagram – a rapidly transmitted disease for the Middle School crowd in Glen Rock, where everyone knows everyone and everyone knows everything, because word spreads fast. The comfort and coziness of posting turned to oblivion. Assuming they could trust the people they shared their “diary” with, students would post about whatever and whomever they wanted.

And often, a seemingly trustworthy confidant would share the post with “outsiders” and cause drama, like the time when a group of girls blocked one of their supposed “friends,” just so she wouldn’t see them hanging out without her. That excluded girl sat behind me in my English class, where I could overhear the conversation with her project partner. “Why weren't you out with your friends yesterday? It looked like fun.” Scanning the room so as not to get caught, this intrusive outsider whipped out her iPhone from her pencil case, and quickly scrolled through her feed, up to the girls’ back-to-back, identical posts of their outing.

Too much silence. I turned ever so slightly. The girl’s fists clenched, her eyes welled up, her focus derailed. I couldn’t predict the course of action she would take:

The anxiety, isolation, and low self-esteem I felt for years continued through high school. FOMO still existed, but the negative feelings latched onto new insecurities – formed by the Instagram platform – about physical image.

Was I pretty enough, skinny enough? Every little thing a woman could nitpick about her body, Instagram made sure to exploit, thanks to the rise of "influencers" – girls who would take cool pictures and endorse cool brands as their jobs. They made money based on their looks.

And their look was the look every high school girl wanted. Some achieved it, usually those who ran in the “popular crowd.” Their prize for equating to these beauty standards? Attention, envy and unspoken power.

The toxic mindset of needing the most likes on a post – because likes meant validation – caused girls to look at each other as competition instead of sisters. The "target" amount started at 100, and as you got older, would go up to 200, to 300. The more likes you got, the more popular you were.

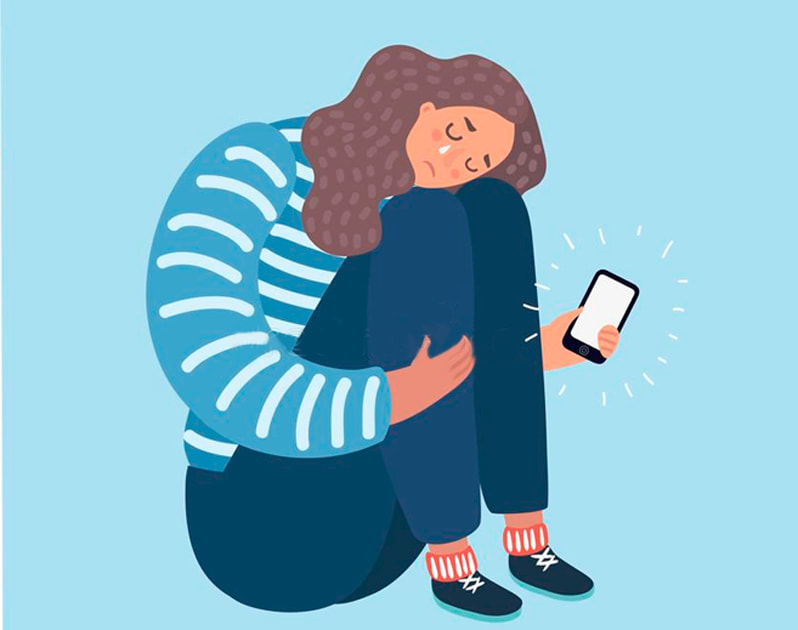

No matter how many likes I got on a post; it would never be enough. I found myself constantly comparing. How many likes did my posts get, compared with the number others who posted at the same time got? And almost everyone found something physically unattractive about themselves to complain about while trying to look their absolute best. All for a faceless, elusive number. Once I got to Bentley University, my posts became funnier, less posed. People would recognize me based on my unique Instagram posts, which encouraged me to keep doing it. I was no longer posting to look perfect. Instead, I wanted to make people laugh, to come up to me and ask about my Instagram post or compliment me, tell me they thought it was funny. But I still wasn’t posting for myself.

I still worried about how my posts would be perceived. During freshman year, friends came and went, and I realized that curating funny posts was too much effort. I wanted to focus on academics, extracurriculars and maintaining friendships. Instagram seemed like a non-priority. This year (2022), people are now able to turn off likes and comments on their Instagram posts, so the misguided association with self-worth might be undone. For me, this feeling of never being enough based on social media has pretty much vanished. I started to post pictures I loved. What would I tell that younger me now? Instagram is now a place where I stay in contact with friends from Glen Rock – from sports teams and classes. Although I once feared that certain people would leave me out or say something negative about me, I now look forward to seeing pictures of them at school or on vacation. When I see a post from an old friend, I am forever grateful for these connections. 👍

|