Learn more about this series.

ANXIETY

|

Christine Moore, GRHS Class of 1999, lives in Hoboken with her husband, and works in publishing and education technology. She is a mentor with Girls Write Now and is consistently learning from her mentee and the program's other inspiring and talented young people how to be a better writer (and how TikTok works... kind of).

|

|

In a pre-Covid November session with my therapist, we had decided that I was ready to try weaning off my anxiety medication. “It should be done during a period of relative stability,” she reminded me – emphasis on the relative because really, when is life ever completely stable? This was as good a time as any.

I had gotten engaged earlier in the year, had chosen my wedding venue, was six months into a new job and was feeling… good. Yes, I had tried to live without Celexa before and every other time had been a failure. But I was feeling more grounded now. I was meditating! (most days) and journaling! (when I remembered to.) I knew the circumstances could never be perfect, but they seemed pretty darn favorable. There was, of course, no way for me to know that this was the absolute worst time imaginable for me to make this attempt. The onset of a global pandemic was an epically terrible time to let my brain chemistry handle things au natural. My anxiety has historically focused on health-related, “what could be wrong with me” concerns and late-night Web MD deep dives, so the thought of a mysterious virus that could spread to everyone I knew and loved sent me into a tailspin. By March 2020, I was back on my medication and slowly coming to the realization that I would probably be medication-bound for the rest of my life.

It took a very long time for me to be okay with taking meds for anxiety – nearly two decades. I had my first panic attack at the Paramus Park mall in the summer of 2000, between my sophomore and junior years of college . I had just purchased a very cute new pair of American Eagle capri pants and matching tube top and was on my way to meet my mom by the carousel. I had a party with some college friends coming up that weekend, and I had to look good, as the boy I had stopped dating a month or so earlier was going to be there.

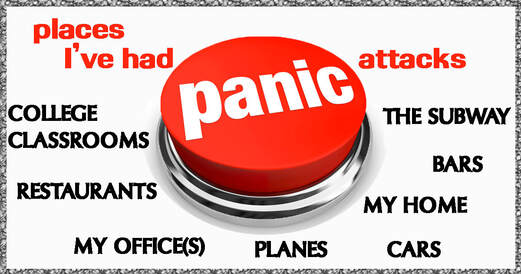

While walking, I suddenly felt as though someone had hit me on the back of the neck. I became lightheaded, started sweating, and my heart was racing. I ran towards my mother, crying, telling her I was having a brain aneurysm (something I’d seen on the TV show "ER.") Mom was not yet well-versed in talking me down and convincing me I was fine. My hysteria was contagious, and she flagged down a mall cop to call an ambulance. The one thing I was certain of – that I have been absolutely certain of every time I’ve had a panic attack since – is that I was going to die. Temporarily calmed by some extremely kind and understanding EMTs, and then again in the hospital by attentive doctors, I was pronounced as fine (physically). In the years since, panic attacks have sent me to the hospital two more times, and I was positive both times that I was in immediate, very real danger. This is the cruel insidiousness of panic – as your mind convinces you that you are doomed, your body responds with all the physical reactions that only serve to bolster this certainty. It’s almost a “tag team” coordinated effort between mind and body Those of us who have panic attacks know that part of the magic is how the attacks become a source of anxiety themselves. In moments of true high anxiety, I am acutely and obsessively focused on myself and my body, on a conviction that there is something wrong with me, physically. I have diagnosed myself with a plethora of conditions over the years, but the only one that stuck is the one I received in a psychiatrist’s office in January 2001, when he read off the symptoms of panic disorder. Every single one of those describes the way I feel, I thought to myself.

As I began to think of myself as a person with an anxiety disorder, and with the help of a wonderful therapist, I looked back on and probed my tendency to throw up whenever I was away from the comforts of home overnight. Whether it was sleepaway camp, a Girl Scout overnight at the Franklin Institute or our 8th grade class trip to Washington, DC, I often found my head in a toilet of some very nice hotel or museum bathroom. Conclusion? My body takes the worries or fears I try to ignore and makes me feel them, physically. Without fail, when I try to ignore any emotional issue, or I’m up at night due to all the things in the world to be anxious about, my body simply won’t let me ignore them. And while I’ve had two decades to become better at handling these reactions, sometimes you just want to ignore the hard stuff… at least for a little while.

Once while driving, I stuck my head out the window like a golden retriever, which strangely did the trick to fend off the panic! My superstitious strategies to ward off attacks have included telling myself, “I won’t eat that meal again,” or “I won’t wear that shirt again.” But the attacks weren’t because my salad didn’t have enough protein, or my sweater was making me too hot.

I have panic attacks because it’s just something that happens to me. Despite this piece’s title, I’m not sure there's an “art” to anxiety – or that I’ve figured out what it is. When I started going to therapy 21 years ago, I was ashamed and hesitant to share this information with anyone. I didn’t even want to take my pills, at first. I would sit on my bed at my parents’ house while my father implored me to do the thing that would make me feel better. “If you had cancer, would you get treatment for it?” he pressed. “Of course, I would!” I sniffled. “Then how is this any different? You feel lousy. This will make it better.” I couldn’t argue with that reasoning. Every year since, I have been thrilled to see the stigma around mental health disorders get a little less intense, and conversations about these challenges become more candid and okay to have. I have managed to think of myself less as a person with a weakness and more of a person with an interesting story — one that might even help other people. My critical self-judgment about “having anxiety” has dissipated over the years and has been replaced with acceptance — even admiration. Perhaps this, then, is the art: loving ourselves despite the hiccups, finding the humor if it’s available to us, and sharing what we can so others can do the same. 😬 😁 |