Learn more about this series.

LETTING GO

|

Harrison Gale, GRHS Class of 2016, is a writer, actor and filmmaker based in New York. Her play, NICE GUYS FINISH LAST, was a second-round selection in 2019's Austin Film Festival Playwriting Competition. In 2020, she was awarded the Andrew Sarris Award for Film Criticism and the William Haller Prize in English Literature. A co-host of the podcast, Do Try This At Home, Harrison holds degrees from University of Oxford and Barnard.

|

|

I don’t remember much of the conversation about how Dad was eventually not going to be Dad. It had been so much easier just being annoyed with my father, so I decided I would just stay annoyed. It was easier to hold on to how I knew him before than to accept the lack of himself that he would become.

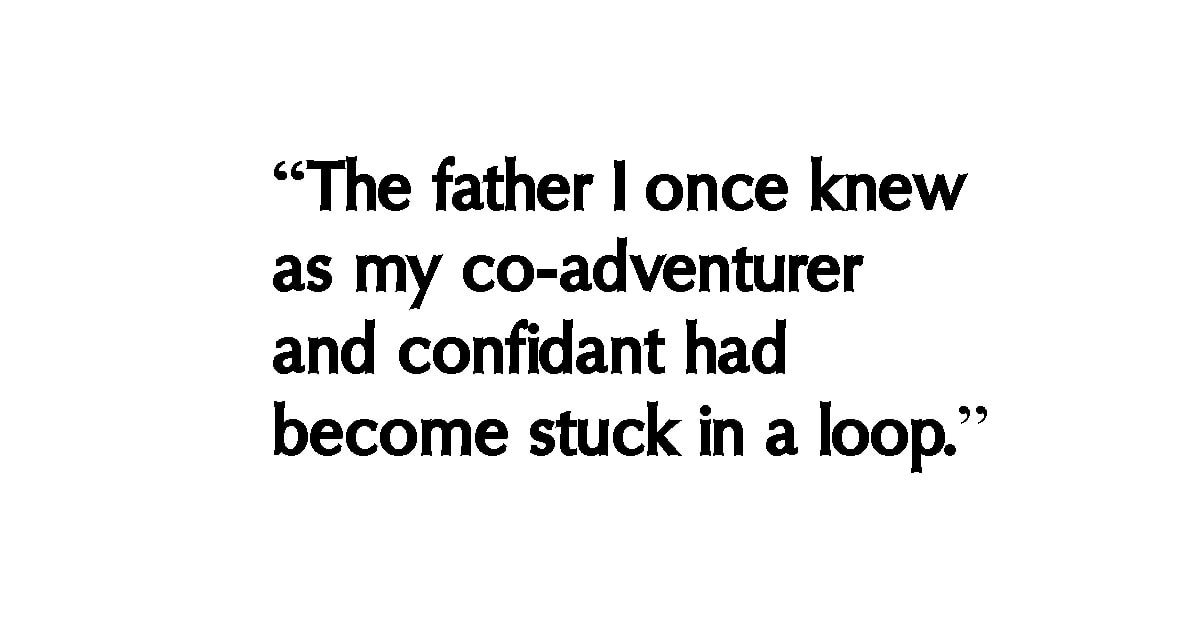

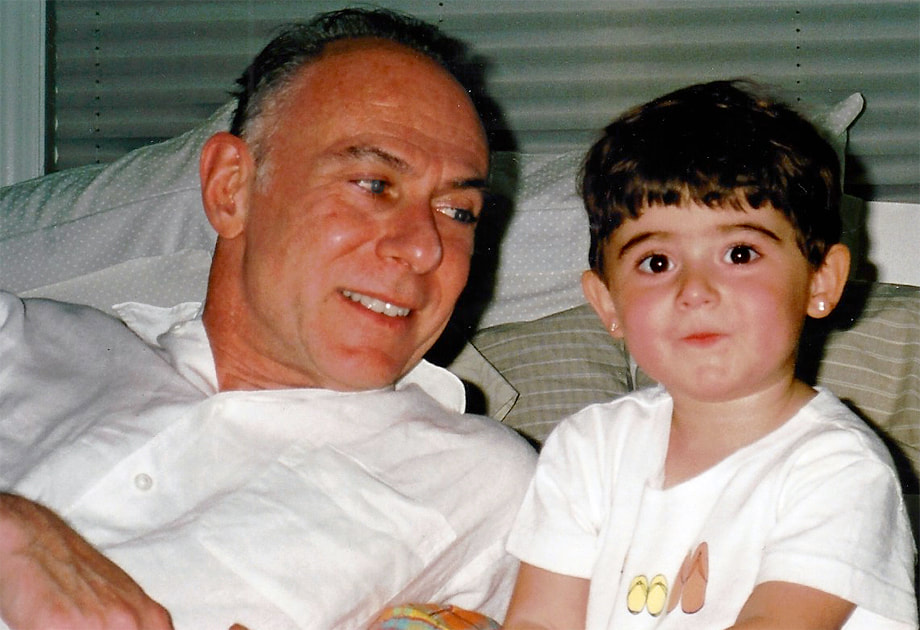

My father, Monte, had been diagnosed with frontal-lobe early-onset dementia. I was 14 years old, and he was 63. My parents and I always “got” each other. I rarely cried in public; I remembered to say “please” and “thank you,” and I pushed myself to do well in school. They always carved out their time for me. Dad made it his mission to play with me every day as soon as he returned from work. Never would I meet any other grown man so eager to dress up in feather boas and sunglasses and hats. But when I inched up to adolescence, the father I once knew as my co-adventurer had suddenly become annoying. This personality shift was so obnoxious to me that it entirely upended our interactions. His goofy humor no longer responded to my typical teenaged social cues like fading laughter or requests to change a conversation topic. A running gag that involved him “speaking” the hidden thoughts of our dog, Jorge, became his primary way of speaking to me. I learned through eavesdropping that his emails to business clients contained oddly constructed sentences with strangely placed prepositions, cycling through a handful of the same nouns and verbs. My dad was stuck in a loop, and by the time I was a freshman in high school, I had accepted it. All dads are supposed to be annoying, right? After two years of his resistance, my mother and I finally convinced him to go to a doctor. We then had the answer to why my father’s personality was near-intolerable, and why he had become so emotionally distant from my mother. I don’t remember the exact moment I learned this, but it was probably in the kitchen of our house in Glen Rock, where the family always discussed important things. It was where I opened my college acceptance letter from Barnard, the last major accomplishment that my father was lucid enough to understand. The only time in my life I ever threw a tantrum was in 2018, the year I turned 20, when my mother told me we had to sell the house I had grown up in. A fall down a flight of stairs had become a daily risk for my father, whose mobility was growing impaired, and a series of poor decisions while he was still president of his small business had put an increasing strain on the family’s finances.

Everything important that had ever happened to me had happened in that house. I cried over my first heartbreak there. The street outside was where I had learned to ride a bike, and also where I first fell off a bike. It was the place my mom and I would stay, wrapped in blankets and watching movies, on days that she’d call in sick to school for me. It was the place I retreated to on the odd weekend when college life felt draining. My love of storytelling was ignited within its walls, when my father was my companion in traversing worlds we created together. I did not know what “home” meant if it didn’t mean that house. On the last day of moving our things out, Mom and I wandered the empty rooms together. My father was already in Puerto Rico with my Aunt Hortensia and our dog – at the home left to Hortensia and my mother by my grandparents. It was November, and the temperature had already dropped. With no furniture to hold in warmth, every room was cold. We walked from room to room, reminiscing in coats, scarves and hats bundled up tightly, our hands shoved in our pockets. That night, we slept on an inflatable mattress in the middle of the kitchen, where our family ate until we were stuffed, where we laughed until our ribs ached, and where we wept until we couldn’t breathe. It was where I learned that my dad was slowly dying. That night was the only night I’ve ever slept in a parka. I let go of that house the way anyone would: by stepping through the front door and closing it behind me.

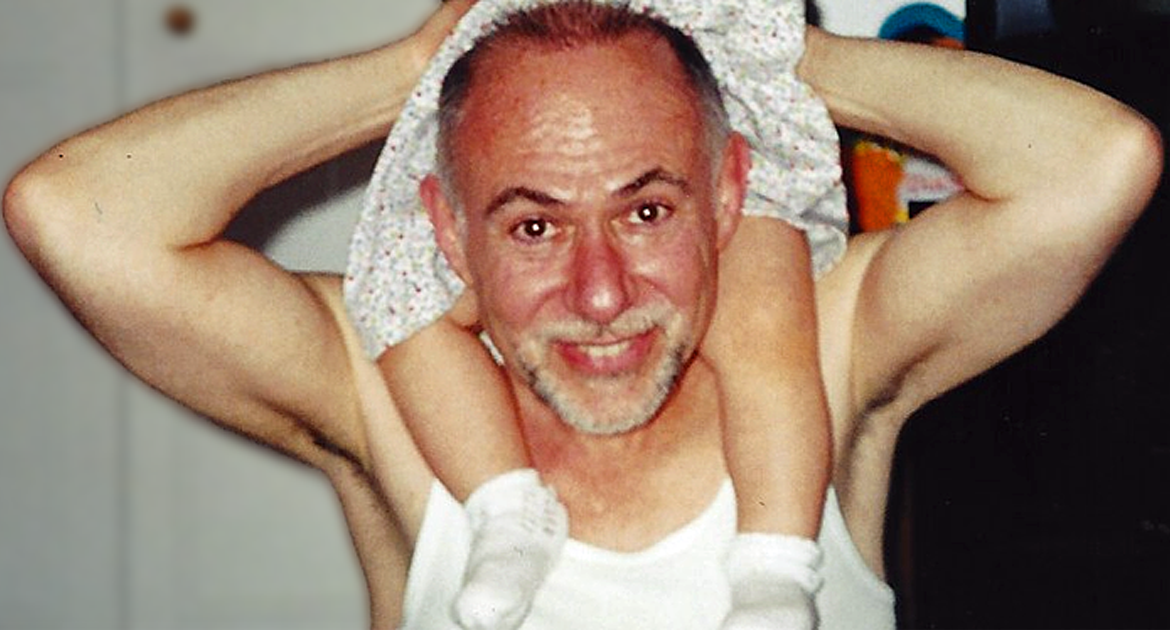

Four years later, I would be rushing to Puerto Rico's HIMA-San Pablo Hospital (late January of this year) in a car driven by my aunt, to see my father lying unconscious in the stroke ward. Though I had been living full-time in New York City, I had recently been staying in Puerto Rico with my mom and aunt to be with them when we took our dog Jorge to the vet for the last time. After years of being a spry and loving miniature schnauzer, Jorge had lost his appetite for life; his body ravaged by diabetes and going blind. We got him when I was 10, and after his 13th birthday in December, I realized I wasn’t really sure how life was supposed to be without him. The veterinarian took one look at him, and knew he was too tired to fight anymore. We needed to be strong for him, strong enough to let him go. As I sat in the passenger seat of Hortensia’s gray Jetta while looking for my father’s DNR, that pesky old chestnut phrase rang in my head: everything happens for a reason.

Jorge brought me here, I thought, as I held my father’s hand, kissed his pallid cheeks, told him all of the reasons I loved him, and watched him labor to push breath through purple lips. Otherwise I would not have been able to say goodbye to my father — who taught me how to love and be loved, taught me how to laugh, taught me how to imagine a world bigger than this one — and that was something I never would have been able to let go. Back when he had the wherewithal, my father had his health care directive written out concretely so that when the end came, the doctors would not be able to put in a breathing tube. A machine would not breathe for him. He would not use a colostomy bag. He had prepared years ago so that when the end came, he could let go, and so could we. I am not the only person to lose a parent young, nor am I the only person to lose a person I loved. Still, I feel the absence and the lack in every fiber of myself. There is a hole in me where my father was that I am never going to fill. But the reason I got up this morning, and the reason I am going to get up tomorrow, and every day after that until I can’t, is because my father was able to let go of what he could not change so that I could do it one day, too.

Helping me give him up — his greatest gift to me — meant allowing me to let go of the guilt, regret and bitterness that came with losing him too soon and slowly. I heard somewhere that closure is being able to remember without pain. I suppose that’s what it means to let go. I’m not there yet, but because of my dad, I know that one day, I will be. 👨👧 |