Learn more about this series.

REVEALING WHAT'S INSIDE

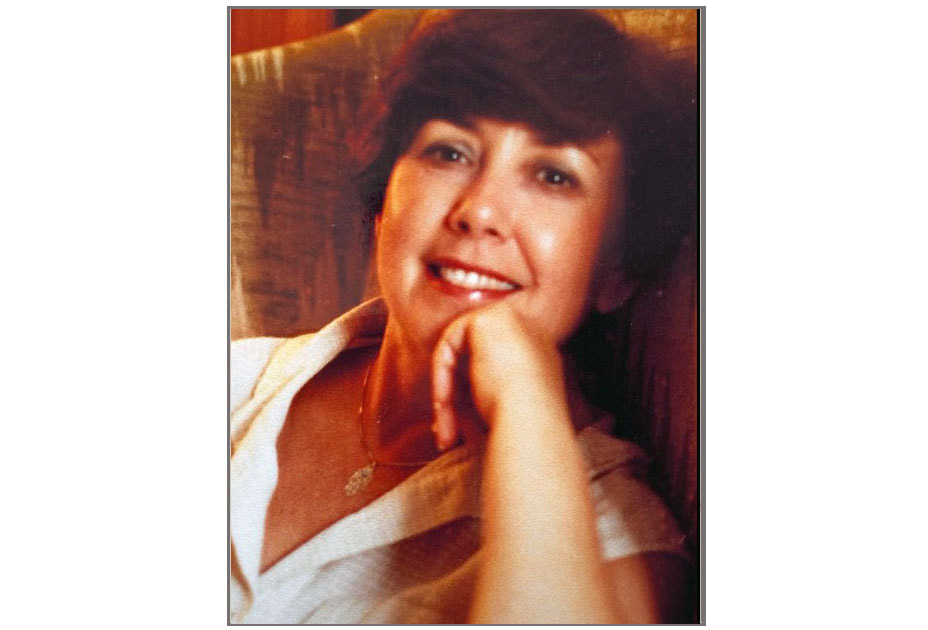

(Remembering Ruth)

(Remembering Ruth)

|

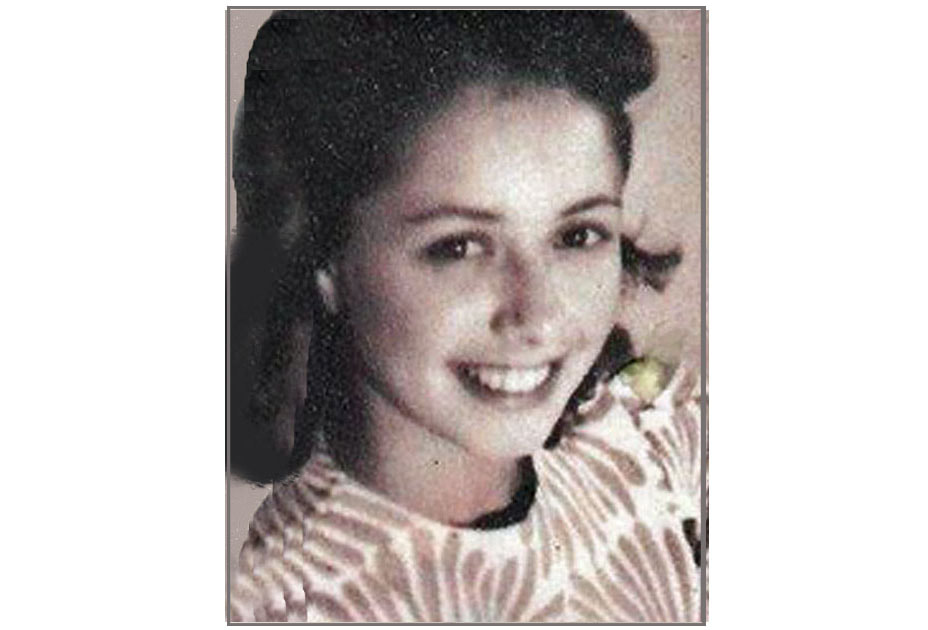

Karen McCollum has lived in Glen Rock for more than 20 years. Her next door neighbor and friend, Ruth Cashman, who lived in Glen Rock for 54 years, passed away at home on December 19, 2021 at the age of 96.

|

|

The phone call came in October as I walked my dog in Martha’s Vineyard. This particular area where we have a beach house has notoriously spotty Wifi, so I rarely pick up when the phone rings. But it was Ruth, my dear friend and elderly next-door neighbor in Glen Rock, struggling with congestive heart failure. I risked a bad connection.

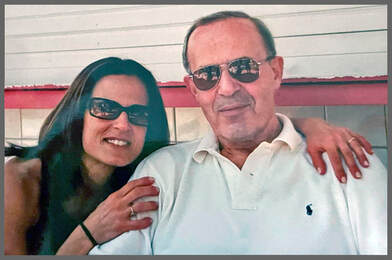

“Karen, it’s Ruth.” Her voice was uncharacteristically weak and breathless, but she spoke with the same authority that defined her. “I am calling, darling, to say goodbye. This is it.” I could hear her loud and clear. I’ve had a conversation like this exactly once before. It was with my father, Dunio, who was handed a devastating diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic cancer at age 68. He died six weeks later. And during those six weeks, I rarely left his side. One day, he was feeling strong. “Let’s go in there. I want to show you some things,” he said. We walked into my childhood bedroom that was now my parents’ home office. He showed me their finances, all the passwords to all their accounts, making sure I wrote them down correctly and telling me what to do with each one. He caught my eye as I was writing furiously, and said, “I don’t know what I’d do without you.” And suddenly we weren’t talking about money anymore. He was saying everything he needed to say to me before it was too late, and for the first time since cancer invaded our lives, we let ourselves cry.

But with Ruth, I couldn’t see her as she spoke to me, couldn’t show her how I felt. I hadn’t seen her in months, hearing from her daughter and another neighbor that she was struggling to breathe and suffered intermittent bouts of pain that began in September. Her damaged heart valves caused her shortness of breath and constant fatigue, and surgery didn't help. She was no longer able to read or paint or do the New York Times crossword puzzles — three of her great passions — because macular degeneration left her legally blind. The Ruth I knew was full of life, sharp as a tack, involved in her book clubs and engaged in current political events. Now, caught off guard on a beach town sidewalk 300 miles away, I stood phone to ear, wrapped up in denial. I managed to say that I loved her and that I’d come see her when I got back. After we hung up, I felt heavy with the weight of regret, wondering if I had somehow disappointed her. My friendship with Ruth began in 1999 when I moved to Glen Rock. She and Morty lived next door. They guided us through the mysteries of what to put out on heavy trash day versus recycling day versus regular garbage day, who to call when the boiler crapped out or the hot water heater burst. Neighbor stuff.

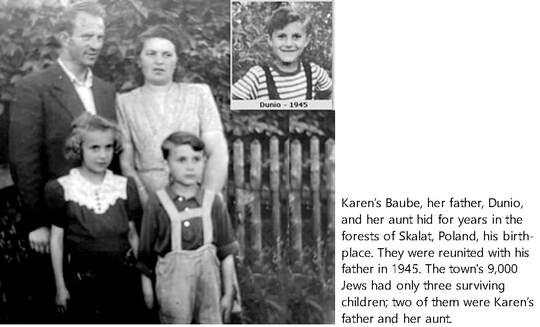

I quickly learned that Ruth wasn’t a gossiper, she was a talker. She said meaningful, not mean, things — casually, almost incidentally. Despite the 41 years that separated our ages, Ruth and I had a lot in common. We fell on the same side of politics and admired many of the same authors, movies and painters. And while she stood maybe 4’9” tall, her intelligence was formidable. Knowing that we might sit together on my front stoop or on her back patio motivated me to read the New York Times a bit more thoroughly than I might have otherwise. She and Morty read it front to back every weekend in their sunroom, which I could see from my kitchen window. When she learned that I came from a family of Holocaust survivors, she engaged in a way most people don’t. She knew the minutiae of World War II, asked impossibly detailed questions, and demanded equally detailed answers. I would often have to call my father, a child survivor, to dig for the info Ruth needed. "What was the exact year you had to leave your house? Where exactly did you hide? For how long? Who took you in that night Baube (his mother) thought it might be your last? Did she know them? How did Baube know when the war ended, and it was safe to go back home? How much longer after that did Zeide come back? How long did you stay in Skalat before you fled to Cuba?”

When you’re the daughter of a survivor, you walk the slippery slope of wanting to know about your parent’s ordeal and being afraid to ask should it bring back unbearable memories. My father’s memories were faint and obscure. He was a baby when the war started, seven when it ended. Most of what he knew came from my grandmother, who would tell the stories in the kind of detail Ruth would’ve appreciated. But Baube died when I was still too young and self-absorbed to fully want to listen. I did my best to piece together the facts Ruth requested.

When we took walks, she listened enthusiastically and laughed at my silly stories about my kids, clapping her hands and raising them to her face so all you saw were her smiling eyes. When she and Morty were preparing to spend time with their son and his family in California, we were living in our basement in the dead of winter with our kindergarten-aged twins, in the middle of a huge 2003 renovation. It had seemed like a good idea... until the contractor had to gut our last functioning bathroom. “Stay here,” said Ruth, offering us her house. “Water my plants. Take in my mail. It’ll be so much better for the kids, for all of you, than a hotel.” Unlike me, Ruth had a very green thumb and tons of plants. I can’t recall if all of them survived under my care. It wasn’t until her funeral that I learned that Ruth did inking for Max Fleischer Studios, where she worked, after high school, on Betty Boop, Popeye, and other cartoons.

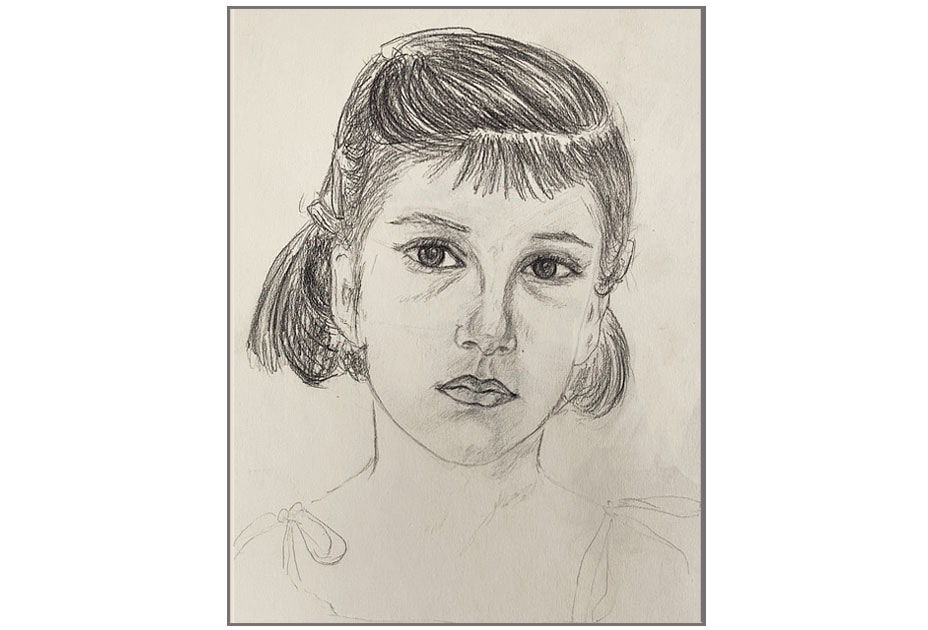

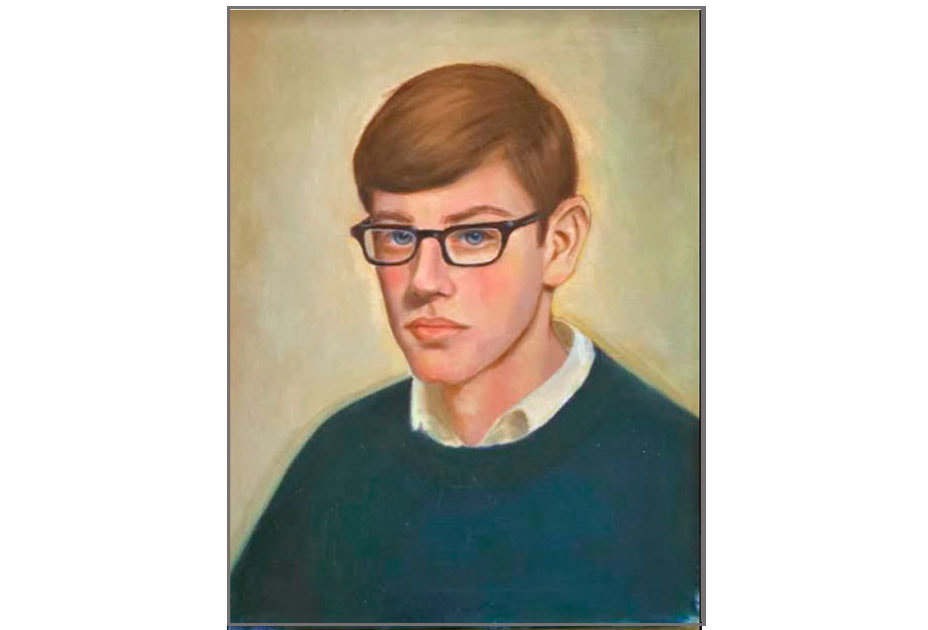

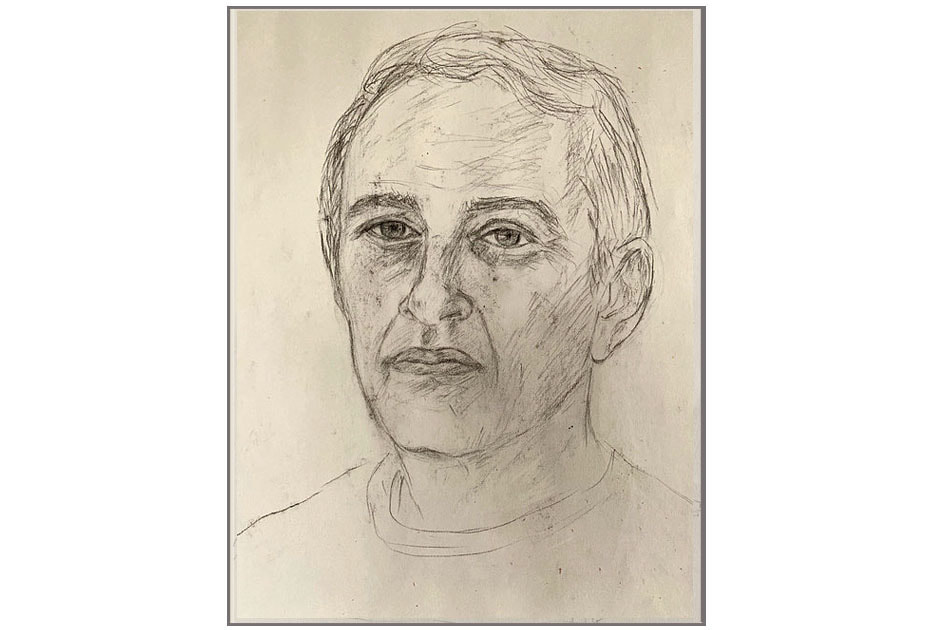

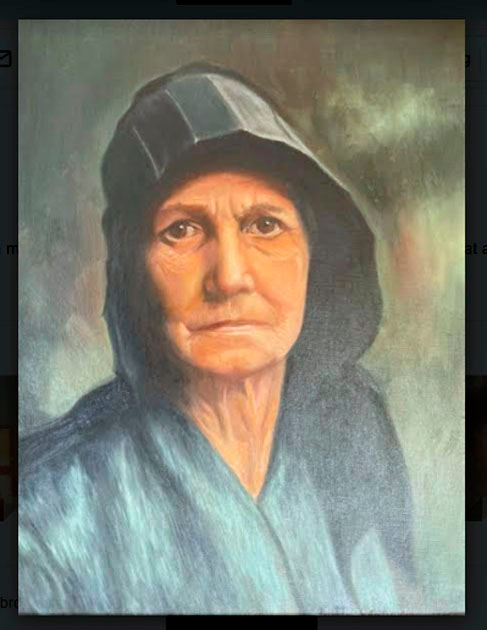

How cool, I thought, how odd that I didn’t know, especially given our shared interest in the arts. But it isn’t odd at all. As much as she wanted to know about my life, she rarely talked about hers. I inferred through conversations that she'd had a difficult childhood in Brooklyn, and from the canvasses that hung in her home, I knew she was a talented painter, even though she’d make that shooing motion with her hand when I complimented her work. Ruth observed and documented what she saw outside of herself, and like a true artist, revealed what was inside her: boundless love for Morty and their children, conveyed in their portraits, and the pathos and untold stories of a hooded older woman painted in oils who was a bit mysterious like her. She didn’t need to speak of her art; it spoke for itself. She had worked in a man’s world with little means or formal education at a time when most women stayed home. What she lacked in formal education she made up for through self-education, reading everything she could get her hands on. One of her recent favorites was Becoming by Michelle Obama. While living in Glen Rock, she took a job as a travel agent so she and Morty could see the world. Their travels spanned five continents and too many countries to count, but a favorite trip was a safari in Kenya.

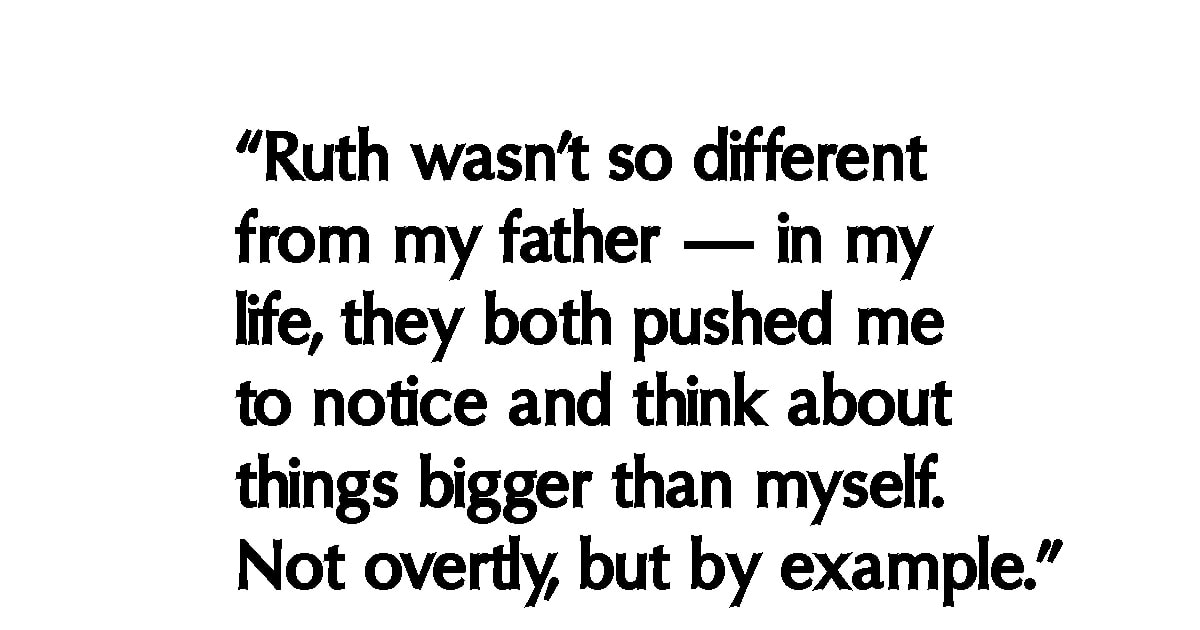

In the same way that my father was smart, direct, unwavering, and courageous, so was Ruth. They embodied all I admire and strive to be. We often find our heroes inadvertently, unexpectedly and for different reasons, and the diminutive woman with the big heart and gigantic mind in the house next door remains one of mine. She’ll live in my heart forever. 🎨 |